The first six chapters of “The Traitor” are

available to read on-line.

Copies of the book can be purchased from

LuLu.com : ISBN 978 1 4092 9076 6

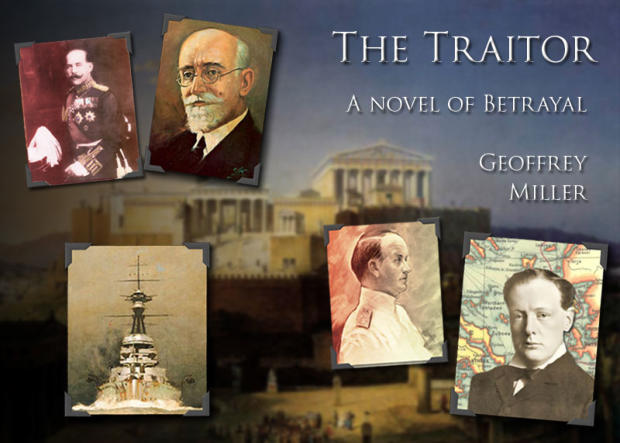

Based on “Superior Force” the acclaimed

study of the escape of Goeben and Breslau

Please feel free to read

this novel but note that

all rights are reserved

and that no part of this

publication may be

further reproduced by

any means without the

prior permission of the

author, Geoffrey Miller,

who has asserted his

right in accordance with

sections 77 and 78 of the

Copyright, Designs and

Patents Act, 1988 to be

identified as the author

of this work.

Contents and Design Copyright 2015 Geoffrey Miller

Contact Information

Telephone

01262 850943

International: + 44 1262 850943

Postal address

The Manor House,

Flamborough,

Bridlington,

East Riding of Yorkshire, YO15 1PD

England.

E-mail

gm@resurgambooks.co.uk

Chapter 3

Salonica

Alexandre Skinas patiently bided his time, a slight tremor in his right hand, as he once more instinctively gripped

the handle of the revolver hidden beneath his jacket, the only outward sign of nervousness. Seated in a squalid

pavement café, he looked up at the scattered broken clouds turning crimson as they reflected the near exhausted

rays of the lowering sun. The greyish-pink buildings of the city, mimicking the clouds, began to turn red also and

he took this to be an omen. He imagined himself looking down at the scene, involved yet curiously detached; the

would-be assassin motionless while, around him, people went about their business as the day drew to a close. He

could visualize a stain spreading — a crimson stain — as if some unknown hand had passed over the scene with a

wash brush. In the near distance a clock struck five; he counted the chimes one by one. The end of the day would

be a good time to die. Nothing, now, could stop him. He knew that, every afternoon, the King walked from the

villa which served as his temporary headquarters, along the seafront, to Beaz Kulé, the White Tower of Salonica.

Once the main pivot of the ancient ramparts, the Tower, the most prominent feature of the city walls, was now

marooned, mute and useless. The walls which had once extended from either side had long since crumbled and

been scavenged, the protection they had once afforded no longer required as the city expanded beyond their limit.

Safety had become a hindrance and Skinas knew that it was the same for King George: he knew that the four

gendarmes detailed to accompany the King had been dismissed on the King’s orders. He knew that the King felt

safe. He thought of the clock once more; of the relentless, unthinking movement of the cogs; he could see, in his

mind’s eye, the equally relentless movement of George of the Hellenes. One step after the other, like clockwork,

marching to his doom.

‘Do you want anything, or do you intend to sit there all day?’ the café proprietor inquired. ‘If you don’t want

anything, push off, so a genuine customer can have that chair.’

Skinas turned around; the café was empty. ‘Business brisk?’ he sneered.

‘I earn my living. I don’t depend on handouts. Push off.’

Skinas jumped to his feet, knocking over the chair in the process. He reached inside his jacket, felt the revolver

handle, and knew that he was a greater man than this café owner, whose destiny he now controlled. One bullet

was all it would take, and the man was too stupid to realize that his life depended on a whim. But Skinas had a

more important task at hand. He accepted the rebuke, even leered uneasily at the café owner, for he knew that,

when he had completed the deed, the worthless wretch would think to himself that he had avoided death by a

whisker. A King had to die so that he may live. Skinas shuffled off, along the harbour wall, until the café owner

disappeared into his filthy kitchen; then he stopped, and waited.

Further along the pavement, as the King slowly came into view, chatting casually with his aide-de-camp, a young

girl rolled a hoop which bobbled and skipped over the cobbled street. Running alongside the King, a familiar

figure since the capture of Salonica by his troops four months previously, the girl remained more intent on her

game. The King broke off his conversation momentarily to follow her progress down the street.

‘What does she know of war, eh, Frangoulis? We have avenged the defeat of ’97; Greeks now control Janina and

Salonica; we are a force to be reckoned with. And she is content with her hoop. That is how it should be. And

tomorrow I am to be honoured by a German battleship here in Salonica. What a fitting climax to my reign.’ The

King smiled.

A tram rattled by. The girl ran on ahead. As she passed the would-be assassin, something caused her to look up at

the emaciated young man perched against the railings protruding from the harbour wall. In that fleeting instant

she saw hatred etched on his face. His dull, fugitive eyes spoke more eloquently than words. Had he not,

Alexandre Skinas, approached the Palace for assistance. Was it his fault that what should have proved a sound

investment on the bourse had failed? Did he not once have a teaching position at the faculty of medicine in

Athens? What did this matter to those behind the gates of the Palace. He had gone, honestly and openly, to ask for

assistance and he had been manhandled by the Palace guard. As a result he was then reduced to begging on the

streets, unacknowledged even by his own family. Now he would show them. Once more he wrapped his hand

around the revolver, as if unsure whether it was still there. Across the street a hawker plied his wares; smoke rose

lethargically from open braziers; people went about their late afternoon business unaware that, in a few seconds, a

foul, premeditated act would rob them of their King. Out in the harbour the German sailors aboard the new battle

cruiser Goeben busied themselves readying the ship for the King’s visit the following day. Their annoyance that so

much, apparently, needed to be done (in the opinion of the junior officers) to such a new ship to prepare for the

visit was tempered by the genuine desire to create a good impression on this, their first official ceremony. Leading

Seaman Steiner, sensing the approach of Lieutenant von Mücke, hastily disposed of his cigarette and picked up

his paint brush, then stopped, mid-stroke, to peer over his shoulder, towards the White Tower. He shivered

involuntarily until von Mücke barked at him to get on with the job; there would be time enough yet to explore the

carnal delights of Salonica.

The moment approached. The clock chimed the quarter-hour. The King passed, barely acknowledging the

presence of Skinas. The revolver was produced. Knees trembling now, Skinas raced up behind the King, placed the

muzzle of the gun against the King’s backbone, and pulled the trigger. It had all been so simple and so quick; too

quick even for shock to register on the King’s face. The bullet entered just below the shoulder blade, pierced the

lungs and heart, and exited from the stomach. The jewelled cross, a permanent feature on the King’s breast, was

instantly smothered with blood. The King collapsed at once and, as he did so, the assassin lowered his aim for a

second shot. Colonel Frangoulis, acting almost without thinking, spun around and grabbed the assassin’s hand.

The man was no more than a bag of bones and, as such, it was a straightforward task to hold him until the arrival

of soldiers alerted by the commotion. Hailing a carriage, Frangoulis gently lowered the stained body of the King

on the seat and they began at once for the hospital; Frangoulis knew it would be in vain. The King’s mouth moved,

bubbling blood, as he strained to say something. Frangoulis put his ear to the King’s lips. ‘No matter … no …’ The

King tried to breathe to form the words; it was no use; his punctured, drowning lungs would not work. With what

breath remained, he whispered slowly, ‘Tell them …’, then stopped, as he appeared to be trying to focus on some

unseen object in the far distance, vainly struggling to recall a long-forgotten and half-suppressed memory. A low

rattle, barely audible above the clattering wheels of the carriage, signalled the end, as his head slumped on his

shoulder. Frangoulis straightened. The King was dead.

A crowd had quickly appeared, to surround the assassin as the soldiers and police grappled with him. Skinas’

momentary anguish at being handled so roughly soon dissipated as he became aware of the gathering. His hatred

dropped like a mask. ‘You have Courts,’ he screamed at no-one in particular, ‘I will speak there.’ At this, one of the

police officers cuffed him about the ears. ‘I have to die somehow as I suffer from neurasthenia,’ he continued, ‘and

therefore I wished to redeem my life.’ Convinced that they would not receive a rational answer for his irrational

deed, the police led Skinas away. As they did he turned his head back towards the crowd. ‘Don’t you see,’ he

implored, ‘the King represents a system counter to your interests. You will see. You will see. You will …’ His voice

trailed away.

Further along the seafront, past the house of the Bulgarian general (for the Bulgarians also claimed Salonica for

themselves, their claim undermined by the fact that the Greeks had captured the city from the Turks a scant few

hours before the arrival of the advancing Bulgarian army), a humble soldier of the Greek King raced to the villa of

Prince Nicholas, the King’s third son, now Military Governor of Salonica. His emotions carrying him forward, the

soldier burst in unannounced on the Prince, realized what he had done, and began to stammer. The Prince,

furious at this intrusion, likewise found himself momentarily at a loss for words. The soldier, regaining some of

his composure, spoke first.

‘They have struck the King!’ he announced, and instantly lowered his head.

At first the words, too horrible to contemplate, failed to register. They have struck the King. His military training

to the fore, Prince Nicholas bade the soldier to control himself. What, precisely, had happened, he demanded to

know? The soldier described the scene and his last sight of the bloodied King, being raced to the hospital. As

much as the Prince wanted to dash off to be at his father’s side, there was one other matter he had to see to.

‘Was it a Bulgarian?’ he demanded.

The soldier looked vacant. His dumb gaze eventually focused, past the imploring Prince, on to the wall behind

Nicholas, replete with fine paintings; to the mantelpiece, with its rare pottery; even to the gilt chair now pushed

back after the Prince had risen to his feet. ‘So this is how they live,’ the soldier thought to himself as he

surreptitiously scratched his crotch. Unlike the other men, he did not mind the cold in his barracks as, he

reasoned, this at least kept the vermin population in check; but this particular louse defied his best efforts to catch

it. He then looked into the face of the Prince; the eyes had narrowed, the mouth contorted as if he was having the

greatest difficulty in forming the words.

‘Was it a Bulgarian?’ Nicholas repeated, trying to restrain himself from physically assaulting this simpleton.

Although still allies in the fight against the Turks there was no love lost between Greeks and Bulgars. The race to

Salonica had been a case in point. Evicting the Turks had been a simple matter; simple when compared to the

question of who should control the city. The occupation by both sets of troops was uneasy enough; murder was a

constant occurrence. Only a few days previously, three Bulgarians, their throats neatly opened, had been found

floating in the harbour, their bodies providing sustenance for the schools of silver fish which pecked greedily at

the rotting flesh. If word spread that the King had been murdered by a Bulgarian it could result in ally finally

turning against ally. It was clear however that the soldier, now trembling in front of him, did not know.

‘Return to your barracks at once,’ ordered the Prince, ‘and tell them the assassin is a Greek. Be off!’

The news of the assassination was received in Athens that night and, by the next morning, was the sole topic of

conversation in the Chanceries of the various foreign Legations. With only the slightest delay, commensurate with

the appropriate display of decorum, the busy little British Minister, Sir Francis Elliot, paid a call on Prince

George, the dead King’s second son, but the only one of whom happened to be in Athens at the time. The new

King, Crown Prince Constantine, was at the head of his troops in Epirus, consolidating the gains made in the

recent war against the Turks, and would soon return; but the Minister could not wait. As soon as news of the

atrocity was received in Whitehall a wire would arrive from the Foreign Office demanding to know how the

assassination would affect the Balkan situation. The “Balkan situation”: how diplomats and politicians loathed

that phrase. At this very moment in London the negotiations to try to end the First Balkan War were dragging on,

characterized by the complete inability of any of the so-called allies to co-operate. Sir Edward Grey, the Foreign

Secretary, was fast losing his patience and he was renowned for his equable temper. It would be sorely tried now.

The dead King had been a staunch friend of England, his sister, Alexandra, the widow of the late King Edward.

With Constantine, however, Elliot was not so sure. Was he not a product of Teutonic training and methods? Were

his inclinations not towards Germany? Most important of all, was he not married to Kaiser Wilhelm’s sister? Sir

Francis realized at once the gravity of the situation. There was nothing he could do about the succession. At the

earliest opportunity, therefore, he must make plain to the new King the fact that Britain, alone of the Great

Powers, had no ambitions in the Balkans, save the maintenance of an increasingly tenuous peace. Sir Francis was

sure that such a highminded, disinterested approach would find favour; whatever the new King’s alleged

proclivities, everyone agreed that he exhibited the straightforwardness of the soldier. He could be made to see

reason.

Riding at anchor in the harbour at Salonica, Goeben, the outward manifestation of German naval power in the

Mediterranean, shifted uneasily as if somehow aware that momentous events were taking place. The decorations

strewn round the ship for the visit of King George now mocked the dead monarch. On the shore, the long line of

low buildings pierced by the massive stump of the White Tower resembled nothing so much now as the leery grin

of an old woman with one tooth remaining. In his cabin Admiral Trummler, the Commander-in-Chief of the

Mittelmeerdivision, pored over a map of the Balkans; like all sailors he was more at home with the lines and

figures on a chart than the contours on a map. Strange, exotic place names — Demir Hissar, Strumica, Monastir,

Florina, Pogradec — lent a certain fascination to the region, even if the political ambitions of some of the states

left him feeling distinctly uneasy. Yet there was no disguising the fact that if Greece could be won over, the

German position in the Balkans would be that much more secure.

While not a politician, Admiral Trummler was only too well aware that the British would be similarly studying

their maps and, he assumed, would be seeking to convert Athens to their cause as a counterweight to German

ascendancy in Constantinople. Perhaps he, a simple sailor, could ascertain precisely where the British stood? Such

initiative would not go unrecognized; nor, he hoped, unrewarded. A successful stint in the Mediterranean would

be a useful addition to his service record. Trummler knew that the British Admiral, Milne, would be sent in his

flagship, the ageing battle cruiser Inflexible, to the Piraeus as the senior British representative at the funeral. If,

Trummler reasoned, he could speak to Milne alone, it would be as a sailor talking to a sailor; there would be no

need for diplomatic euphemisms. Such thoughts were still on his mind as Goeben eased out of the harbour, in the

wake of the Greek Royal Yacht, Amphitrite, on the mournful journey to the Piraeus taking the King’s body first

back to Athens and finally to his beloved Tatöi, the Royal Family’s private retreat in the hills above the capital. A

thick fog, such as people could scarcely recall, cloaked Salonica in a ghostly shroud as the procession left the

invisible land behind. Steaming slowly out into the gulf, Amphitrite and her escorts — Goeben, HMS Yarmouth,

the Italian cruiser San Giorgio, the Austrian cruiser Maria Theresia, the Russian gunboat Uraletz, and the French

cruiser Bruix — were soon lost to each other’s view. There was no alternative now but to heave to, for safety’s sake,

and drop anchor waiting for the fog to lift.

All was quiet on the water save for the elegiac toll of the ships’ bells. Aboard the Royal Yacht the King’s body, still

clad in the uniform he had been wearing when the assassin struck (as it had been found impossible to undress

him) bore the same expression of serenity which had descended upon his countenance at the moment of death.

For he had succeeded in recalling the forgotten memory of his childhood, and the large, lumbering, good-natured

puppy he had called Oscar, after a jowly uncle. He had teased Oscar unmercifully until the tormented dog, unable

to take any more, had placed its giant paws on his shoulders, had knocked him to the ground, and had then stood

menacingly over him. Aware that he was now in command, the dog then licked his tormentor’s face until the

Governess, alerted by the boy’s screams, had raced in to see the cause of the latest commotion. Realizing at once

that the patience of the dog had been tried beyond endurance, she had refused to intervene; nor would his

mother, who arrived soon after. Oscar, content now that he had exacted retribution in the form of the humiliation

of his little master, carefully withdrew from his position of superiority and sat faithfully by the boy’s side. The two

remained inseparable from that point on, until, following the dog’s eventual demise, he was given what

constituted, in his master’s eyes, a Royal funeral.

Admiral Sir Archibald Berkeley Milne, the Commander-in-Chief of the British Mediterranean Squadron, felt a

certain tinge of embarrassment as his flagship glided into the Piraeus. It was the first time he had seen his

principle adversary at close quarters and there was no doubting that Goeben was a magnificent ship. He had, he

thought reflectively, been born twenty years too late. The Mediterranean Squadron at the turn of the century had

been a prize worth having. Since the recall of the battleships and the subsequent confusion following Winston’s

meddling the previous year (the very idea of having nothing larger than a cruiser in the Middle Sea was

preposterous), the Admiralty had been in continual skirmish with the Foreign Office. Yet, paradoxically, it was the

Foreign Office which wanted the naval strength in the Mediterranean increased, for diplomatic purposes, while

the Admiralty wanted every available capital ship in the North Sea, to counter the threat from Germany. Now,

until a compromise could be reached, his command often consisted of no more than his own battle cruiser and a

few humble destroyers. That this had been enough to lure the German battle cruiser from the North Sea gave him

scant satisfaction. Malta, it was true, had its delights but he would gladly have surrendered these for the

command of a real fleet. He could not, naturally, divulge the slightest hint of his true feelings to the German

Admiral, for Trummler had requested permission, rapidly granted, to pay an official visit upon Inflexible.

On April Fool’s Day, 1913, Admiral Trummler was piped on board and ushered into Milne’s cabin. The dark wood

panelling was warm and comforting; a few books, mostly novels of the more popular kind and showing few signs

of being read, lined the shelf above the heavy, carved desk. This was not, Trummler thought to himself, the cabin

of one with an abiding interest in the current diplomatic situation. Even so, he knew that Milne still had some

influence at Court and could have whatever information Trummler cared to divulge whispered in the appropriate

quarter. Milne directed Trummler towards the leather sofa as they continued to weigh each other up. The British

Admiral lived up to his reputation as a dandy. Immaculately attired, his neat beard perfectly trimmed, even the

proportion of grey hair to brown seemed to be part of a carefully pre-ordained, dignified design. Spoiling the

overall impression of a caricature admiral however were two narrow, restless eyes. Trummler momentarily had

the feeling that Milne was not looking at him, but through him. Despite appearances, this was not a man to be

trifled with.

‘A bad business,’ Trummler began.

‘Yes, I am afraid that, in this part of the world, assassination is looked upon as a legitimate part of politics,’ Milne

answered in a tone that readily denoted his disgust. ‘Why wait for an election or whatever, eh, when a well

directed bullet will do the trick. Their last Prime Minister went the same way, did he not?’

‘And now, we,’ Trummler continued, ‘who conduct our affairs in a more civilized fashion, are left to exert our

calming influence, knowing all the while that, if not today or tomorrow, soon, the situation will be just as fraught

after some other atrocity. I sometimes wonder why we do not simply cut these accursed states loose though,

doubtless, my Foreign Office would disagree. If I may venture, I believe that you British feel the same way.’

Admiral Milne nodded agreement and permitted himself a thoughtful grin while framing his answer. ‘We seek no

territorial advancement, of course. I sometimes wonder, in fact, if the onerous responsibility of Empire is not too

great. No — we desire to use our influence to the benefit of backward peoples; however, some are more ripe to

benefiting than others. If I may venture a purely private opinion, the true civilizing influence of our culture is felt

in Africa and on the sub-continent, not in the Balkans. We leave that area to our …’ A somewhat theatrical pause

followed, as Milne recalled the various Agreements, Ententes and Conventions uniting the Powers. ‘I cannot call

them our allies, can I?’ he answered himself, deprecatingly. ‘To our partners then, the French and Russians: their

interest in the Balkans rather drags us along.’

Trummler also found himself weighing up the advantages of possessing allies whose effect he believed was not to

act as props, but rather as burdensome liabilities. ‘It is all very well to give them a free reign in that area, and the

French may be made to listen to reason, but the time will come when you will be called upon to restrain the

Russians. When the time arrives, as surely it must, will you be capable of doing so?’

‘We will be about as capable as you will be of restraining the Austrians.’

‘I take your point,’ and now Trummler smiled. ‘A headstrong lot, the Russians and the Austrians. From my

experience, the weaker a nation is the more it depends on bombast and threats. What was it the American

President said? Ah yes, “speak softly and carry a big stick”. St Petersburg and Vienna lack the big stick, do they

not? A pity, in so many ways, that what I might call the ‘two great white races’ could not align themselves. Many of

my colleagues strongly desired an Anglo-German alliance, you know. Instead, one grouping of Powers surrounds

the other and we all arm and train and build ships we cannot afford. And for what? So that we may fight over a

desolate piece of land in a country that no-one has heard of, just to be able to add another name to the tally of

colonies kept so scrupulously in Whitehall and the Wilhelmstrasse.’

As unexpected as this admission was, Milne still believed Trummler was not as contemptuously dismissive of

German colonial ambitions as he made out. There was one way to find out. A recent cable from the Admiralty had

reported unrest in the Levant. Such unrest, as Milne well knew, was a perfect pretext for any of the Powers to

move in on the spurious grounds of protecting their interests. And, after Germany, the country that required the

slimmest of pretexts was France.

‘A tally also kept in the Quai d’Orsay,’ ventured Milne. ‘I have it on the surest authority that the French will use

the current unrest in Lebanon as an excuse to, if I may use such a tabooed expression, extend their “sphere of

influence” in Syria. While we have been in the past quite content to trade French interests in Morocco against

British interests in Egypt, I am quite sure neither of us would welcome a heightened French presence in Syria,

particularly so just now, when the Baghdad Railway negotiations are so delicately poised. I myself am ordered

back to Malta after the funeral, or I would put the proposition to my superiors. However, I am free to urge you to

send some of your ships to the region. A cruiser off Mersina and another one, at the very least, off Alexandretta,

would, I believe, forestall any immediate French move.’

Trummler looked hard at Milne, trying to perceive in his demeanour any intimation as to the reasoning behind

this unexpected request. ‘I am obliged for this information, Admiral. Obliged and, may I say, somewhat surprised.

You are, it would appear, as suspicious of French intentions as we, and with good cause, I imagine. If only our

Foreign Ministers could hear us! I personally should rejoice if we show more interest in Asia Minor by increasing

our number of ships. If we wish to have a share in cutting up Asia Minor when it comes off, it will do the other

claimants good to find that we are not to be pushed on one side. But, for the sake of international harmony, these

naval demonstrations ought to be restricted to such points as undoubtedly belong to our sphere of interest, and,

unfortunately, no one in Berlin so far has determined precisely what part of Asia Minor we intend to claim as our

own!’

The two Admirals laughed, and were still laughing as they rose from the sofa. ‘I will inform my Foreign Office, but

I fear they will be content to leave the French alone. Perhaps,’ Trummler hesitatingly inquired, ‘we could continue

this discussion tomorrow?’

‘At the funeral?’

‘A trifle insensitive, I admit, but it would not do for me to be seen paying too many visits upon the British

Commander-in-Chief.’

The King’s body lay in the open coffin as a constant line of respectful Greeks silently filed past, some pausing to

kiss the corpse’s outstretched hand. This planting of lips on cold, clammy skin would be their only contact with

royalty in their entire lives. On a narrow dais behind his father’s body stood, immobile, the new King, with his

wife and children at his side. Behind him, on a lower level, his unctuous private secretary, George Melas, clearly

relishing the fact that he now served a King instead of a mere Crown Prince, nodded knowingly at the occasional

dignitary. It would fall to him now to control the King’s official appointment diary. Even Prime Minister Venizelos

could only approach the King through him. He was certain also rapidly to be issued invitations to visit the various

Legations; to talk directly to the Ministers; and to sample a lifestyle somewhat more sophisticated than the

austere regime favoured by the new King. Prince Demidoff had brought his own chef with him to the Russian

Legation — the dinners there were reputed to put even those at the Hotel Grand Bretagne to shame. And then, of

course, there was the famed wine cellar at the French Legation …

George Melas acknowledged another greeting; he could now make his mark in the world. Outside the Cathedral

the drizzle had turned to steady rain. For hours, the Greeks waited patiently to honour the imported King. In

death he was now their equal. As the rain gathered up the dust from the streets and washed it away, a few of those

standing there were reminded of the prophecy: that Greece would retake Constantinople when there sat on the

throne a Monarch by the name of Constantine and a Queen by the name of Sophie. Now it had come to pass.

Everywhere, in their tenuous foothold in Europe, the Turks were being beaten back — beaten back to the very

walls of Constantinople. If ever that age old dream were to be realized, it would be now.

On the day of the funeral, the majority of the mourners were silent with their own thoughts. Among the ranks of

those paying their last respects however, two bejewelled admirals in full dress uniform could be seen in hushed

yet animated conversation during the interminable ceremony. By the end of it, Milne was sure that the German

scheme encompassed not only the spreading of their tentacles throughout the Ottoman Empire, but also now,

through the Balkans. There was nothing concrete; no phrase or sentence that he could repeat and say, ‘There, here

is the proof!’ Just an accretion of facts and hypotheses, paramount of which was the necessity for Berlin to gain

control of the Balkan causeway and Ottoman Empire, and so prevent the complete encirclement of Germany and

Austria-Hungary by Russia and her partners. The more adherents to the German cause, the longer the Russians

could be held at bay while the French were dealt with first. Bulgaria was in their hands already; Greece was to be

next. Milne did not have long to wait for confirmation of these fears. Early in May he learnt that Trummler had

indeed proceeded, in Goeben, to Mersina. The Kaiser himself was later to remark to the British Naval Attaché of

how pleased he was that Milne’s timely hint had meant that the German ships had arrived just in time to prevent

what he referred to as “an Armenian trouble”. For all Trummler’s bonhomie, Milne now knew that German

designs on Turkey were well mapped out. A sphere of interest undoubtedly existed, if only, for the time being, one

coloured on the maps in the German Foreign Office. And the same colour was now to be applied to Greece. Soon

after, Milne learned, through an agent employed by the British Legation in Athens, that German contractors were

swarming around the Greek Ministries of Marine and War, with artificially low tenders in their briefcases for new

howitzers, machine guns, submarines and battleships, all underwritten by the Imperial German Government. This

was how it began — control the military and you control the Government.