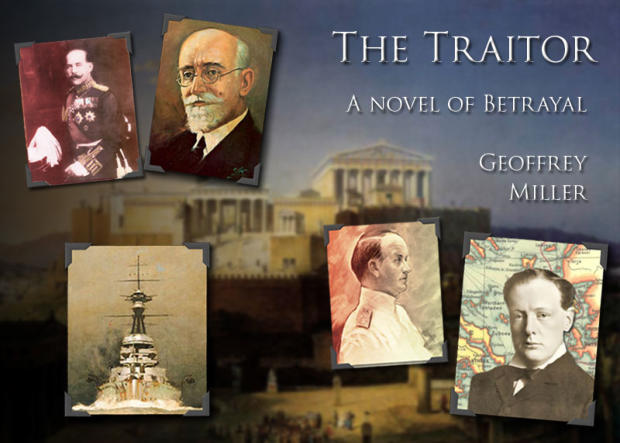

The first six chapters of “The Traitor” are

available to read on-line.

Copies of the book can be purchased from

LuLu.com : ISBN 978 1 4092 9076 6

Based on “Superior Force” the acclaimed

study of the escape of Goeben and Breslau

Please feel free to read

this novel but note that

all rights are reserved

and that no part of this

publication may be

further reproduced by

any means without the

prior permission of the

author, Geoffrey Miller,

who has asserted his

right in accordance with

sections 77 and 78 of the

Copyright, Designs and

Patents Act, 1988 to be

identified as the author

of this work.

Contents and Design Copyright 2015 Geoffrey Miller

Contact Information

Telephone

01262 850943

International: + 44 1262 850943

Postal address

The Manor House,

Flamborough,

Bridlington,

East Riding of Yorkshire, YO15 1PD

England.

E-mail

gm@resurgambooks.co.uk

Chapter 4

Whitehall

London looked as grey as only London can. Although the middle of March, Spring seemed as far away as ever.

People scurried by, eager to spend as little time as possible in the raw, biting wind. On the steps of the National

Gallery a small group huddled together, waiting for their guide, looked out across Trafalgar Square, severe and

uninviting, and down Whitehall. While they sheltered, the business of Empire was conducted by frock-coated civil

servants and their political masters in dark, warm offices. In his room at the Foreign Office Sir Edward Grey,

burdened by the ever-present ghosts of former Foreign Secretaries, paced the floor. Exhausted, careworn, he

disliked the thought of the seemingly endless Conference of Ambassadors to settle the Balkan War and longed to

return to Fallodon, his Northumbrian estate. Had he not wanted the Conference to be held in Paris so that he

could then delegate the chairmanship to Frank Bertie from the Embassy? The one saving grace was that Easter

would fall particularly early, on 23 March, and there was one thing which was sacrosanct to Sir Edward Grey: the

proper observance of holidays.

Not that he was in any way religious. What residue of religion remained from the inculcation of childhood had

been destroyed when, seven years previously, his wife had been catapulted from her carriage near Fallodon after

the horse, whose nervous state she had been warned about, had bolted. Sir Edward had been at a meeting of the

Defence Committee when news was brought to him (Lady Dorothy had cared little for London society, preferring

to remain at Fallodon even when the House was sitting) and it had taken him half a day to return. By the time he

had entered the small schoolhouse in Ellingham, to which she had been carried unconscious, the paralysis had

already spread down her left side. He longed for her to speak, even prayed for it, as he sat by her side for two days.

That prayer — the last he had ever uttered — went unanswered, as Dorothy succumbed without regaining

consciousness. With her went his faith.

A window rattling in the wind brought Sir Edward back to the present, and to the Balkan War. Although most of

the fighting had ceased, the Allies were in the process of falling out amongst themselves over the spoils. And now

this. In addition to the report from Elliot in Athens, he held another in his hand from Lowther in Constantinople.

There were rumours at the Porte that the assassination of the King of Greece was not solely the work of a

deranged madman, but that a conspiracy involving Austria was at the back of the deed and, worse, that political

circles in Athens had been forewarned of the attempt. If true, and Grey fervently hoped that they were not, the

conspiracy must reach to the very top, to Premier Venizelos. Grey had little time for the Greeks in general, but he

thought he could trust Venizelos.

His great failing, recognized but tolerated by Asquith, whose own judgment occasionally fell short of that expected

of a Prime Minister, was a too-trusting nature. Affairs of state, he believed, could be conducted on the same basis

as personal relations; not even seven years in his present post had been sufficient completely to disabuse him of

this fantastic notion although, it is true, he had been sorely tried by the machinations of Isvolsky, Sazonov,

numerous Grand Viziers, and almost all the Balkan rulers. But not, until now, Venizelos. He must know, one way

or the other. The Foreign Secretary summoned Sir Arthur Nicolson.

The stooped figure of the Permanent Under-Secretary eventually shuffled in. His brilliant blue eyes still spoke

eloquently of an active, alert mind; however, crippled by arthritis and worn down by anxiety, Sir Arthur now

longed to finish his days as Ambassador in Paris once Bertie’s tenure was up. Although his keen sense of duty kept

him at his current post it was now a job for a younger man. The Anglo-Russian rapprochement, his crowning

achievement, was firmly in place and he had lost whatever patience he had had with the Balkans.

‘What do you make of this?’ Grey calmly inquired.

Sir Arthur cast a weary eye over the dispatch, making as if to read it, to refresh his memory. He had known that

there would be trouble as soon as the dispatch had arrived. ‘Lowther reports every rumour that emanates from

Stamboul. He should learn to be more discriminating; doubtless he is tired.’ Nicolson knew well from his private

correspondence with Lowther how much the Ambassador, after five years at the Porte, had come to hate his

posting.

‘So you place no faith in it?’ Grey inquired hopefully.

‘Oh, there may be something in it. It makes such little sense otherwise. We have grown used to anarchist outrages

in oppressed states, but from all accounts King George was a popular Monarch, especially so following the recent

military success. Had the King been struck down by a Bulgarian or a Turk the motive would have been clear and

obvious. That it was, apparently, a Greek causes me some unease. As for the supposed warning, Venizelos is a true

Cretan in that scheming is second nature to him; but to connive in regicide is to impute such base motives that I

cannot accept the Premier’s guilt. Certainly not on the evidence contained in Lowther’s wire.’

Grey looked anew at Nicolson: ‘Have you heard anything privately?’

‘What do you mean?’ Nicolson attempted, without great success, to avoid Grey’s gaze.

‘My dear Arthur, I am well aware that Fitzmaurice supplies you with snippets of information. He appears to me to

wield far too much power for an Embassy Dragoman. Lowther relies on him too much. I have cautioned him

before on the subject. But he does have sources of intelligence denied the remainder of the Embassy staff. Has

Fitzmaurice reported on anything which would lend credence to Lowther’s “rumours”?’

‘Nothing I am aware of,’ Nicolson lied, none too convincingly.

Grey picked up the copy of the Ambassador’s cable and read it through again, while Nicolson focussed on the

delicate painting of a Moghul prince on the wall behind the Foreign Secretary. How much simpler life was then, he

thought; how complicated and tedious now. To have been present at the Court of the Imperial …

Grey pinched the bridge of his nose and blinked slowly. ‘I am, as you are aware, not at all satisfied with Lowther’s

performance. He appears to alternate between lassitude and bouts of hysteria to an excessive degree; it is an

unhealthy combination. I cannot say that his five years’ tenure at the Porte has been an unqualified success.’

Nicolson realized at once where the conversation was heading, his moist blue eyes now staring intently at Grey:

‘You have thought about a successor?’

‘I think it is important to show the Turks that we still value their friendship. Naturally, it was impossible to accede

to any of Tewfik’s requests for an alliance; however, an appointment from within the Office, rather than from the

diplomatic corps, would, I believe, send a tangible signal to the Grand Vizier that we mean to embark on a new

course. And, if the new Ambassador was of a suitable standing, it may help to counter the German influence at the

Porte.’ Sir Edward then stood silently in front of the large wall map and stared impassively at the coloured area

denoting the Ottoman Empire. Putting his finger on the Persian Gulf, the Foreign Secretary traced the route of the

Berlin to Baghdad Railway back from its terminus in Basra to Haidar Pasha in Constantinople, then, from across

the Bosphorus, the line snaked up through the Balkans. He looked at Germany, coloured green on the map, and

imagined for a moment the green ink spilling out over the German border through Austria-Hungary to Roumania,

then Bulgaria, then Turkey-in-Europe, until it finally flooded out across Asia Minor and lapped at the very border

with India. If that happened, the only means of launching an attack to safeguard India would be via Greece or

Serbia. But Serbia was landlocked; Britain’s naval might would be impotent. Greece was the key to the situation. It

was obvious, even to someone as unschooled in military matters as Grey: from Greece, a combined attack could be

launched through the Dardanelles, to sever the enemy’s supply line. Once the flow of reinforcements had thereby

been halted, the Indian Army could go on the offensive. There were times when Grey wondered why more heed

was not paid to his opinions in debate at the Committee of Imperial Defence.

During Grey’s meditation, Nicolson had also been immersed in his own thoughts. Grey turned to face him: ‘Upon

your retirement Arthur, and we have to consider such matters now, in ample time, one name will go forward for

your post. I would prefer that name to be Crowe’s.’

Nicolson was both shocked and relieved: ‘So Mallet is to go to Constantinople?’

‘Yes, Mallet has become too set in his ways here. His recent minutes have not been edifying. If a certain lethargy

has overcome him perhaps a sojourn at the Porte might be the stimulation he requires. I have given the matter

considerable thought: nothing must stand in Crowe’s way. When Lowther’s post becomes vacant this summer I

intend that Mallet should go out to replace him.’

Who will then take over the Eastern Department?’

‘That will become Crowe’s responsibility as well.’

Nicolson had not expected this: ‘In addition to the Western Department? That would be an onerous burden.’

‘No-one is better qualified than Crowe to shoulder such a burden. In fact, his work in the Eastern Department will

commence immediately, though, for the present, this will be known only to you and I. You should also know that I

have asked Crowe to attend this meeting as I have a task — a test if you like — for him. It is a task involving

judgment and some delicacy. If he succeeds there will be no barrier left to prevent his advancement to Permanent

Under-Secretary.’

‘And if he fails?’ The question had to be asked for, with Mallet dispatched to Constantinople, there would be now

no other logical successor.

Grey looked at the map again. ‘If he fails, war becomes inevitable.’ The silence which followed was finally

punctuated by a sharp rap at the door. The upright figure of the Assistant Under-Secretary strode into the room.

Crowe was one of those people who look efficient. He had devoted his life to the Office and already the strain was

beginning to tell, the lines etched deeply on his face making him look distinctly older than his thirty-nine years.

His whole air was one of briskness and intelligence, a product of his Teutonic upbringing, but which tended to

mask an innate kindliness. This last quality was all but successfully disguised from his peers but could not be

hidden from the younger members of the staff amongst whom Crowe was renowned for his thoughtfulness.

While Sir Arthur sat with head bowed, Grey repeated his fears about the Balkan situation and of the rumour

contained in Lowther’s cable.

‘Well Crowe — what is your opinion?’

Crowe had had a shrewd idea as to why he was being summoned and had prepared for the meeting by reading all

of Elliot’s dispatches from Athens for the past month. Without pausing, he began to answer Sir Edward: ‘For the

moment, it would be impossible to consider what motive Venizelos might have for conspiring or failing to act on

any warnings. As far as I am aware, the King and Premier generally saw eye to eye, yet, as the result of this

assassination, Crown Prince Constantine is now elevated to the throne. One must assume that he would lean

towards Germany and that, therefore, a gulf may appear between him and Venizelos. On a purely hypothetical

level, Venizelos might welcome such a gulf if his ultimate aim is to move towards a republic … ’

‘Surely that is being too cynical?’ Grey interrupted.

‘I am afraid, Sir Edward, that when it comes to the Balkans, it is impossible to be too cynical.’

Grey moved across to his chair and sat down; leaning forward he picked up a large, silver-mounted ivory

paperknife and gripped it so tightly that his knuckles turned white. ‘I must know if there is something behind this

dreadful act. Did Austria have a hand in the assassination? Was Venizelos aware of the plot, if plot there were?

Who stands to gain?’ He relaxed his grip on the paperknife slightly. ‘Do we have anyone who could report

privately from Athens? I do not want to involve Elliot; in any case, I know that he rather abhors this side of his

duties.’

Crowe and Nicolson looked at each other, waiting for one to speak. If anything, Nicolson shared Elliot’s

misgivings as to this side of foreign affairs. “Spying” had such unfortunate connotations. Crowe, perhaps sensing

his reticence, spoke up: ‘Our best man in the Balkans is Samson, Major Samson. He is currently working incognito

as vice-consul in Adrianople, reporting on the siege.’

‘He could conduct inquiries with absolute discretion?’ Grey inquired tentatively.

‘I am convinced of it,’ replied Crowe, who valued Samson’s work more highly than that of any of the military

consuls whose reports crossed his desk.

‘Very well. I entrust the matter to you. Re-assign Samson to Athens. Instruct him to instigate confidential

inquiries into the assassination. I want to know upon whom I may rely in the Balkans. Above all, is Venizelos to be

trusted?’ Almost as an afterthought, Grey added: ‘Liaise with the War Office, of course.’

Crowe allowed himself a sly look at Nicolson as they took their leave. There was only one Government Department

with which, in their dealings, they experienced more trials than the War Office, and that was the Admiralty. The

great departments of War held such ossified ideas as to the conduct of diplomacy. This was the twentieth century,

after all. Of what use were battleships when every navy possessed battleships; of what use were machine guns and

howitzers when every army possessed such weapons?

Once they were outside the Foreign Secretary’s room, Nicolson beckoned to Crowe. The Permanent Under-

Secretary removed an envelope from an inside pocket and handed it to his protégé: ‘Here, read this, note the

contents, and return it to me at your earliest convenience.’

Crowe looked at the envelope with its unmistakable handwriting and saw at once that it was a private letter from

Fitzmaurice in Constantinople. He returned Nicolson’s frown: ‘But surely, Sir Arthur, this is a private

correspondence?’

‘Read it,’ Nicolson replied emphatically, ‘you need to be aware of what is going on. Do not fail me, Crowe; there is

too much at stake.’

Crowe, who had never before seen Nicolson so rattled, returned to his office to study the letter:

“British Embassy,

Constantinople,

15 March 1913.

My dear Sir Arthur,

As I once told you, a dragoman is merged in his chief and as I have only politics to write about, one is afraid of

saying something which may not fit in with one’s chief’s views. I must however revert to the recent dispatch of Sir

Gerard, in which mention is made of the plot against the life of King George of the Hellenes. As this intelligence

was obtained by myself, I feel able therefore, to inform you, very privately, of the circumstances in which it was

obtained, as they are somewhat more involved than those alluded to by Sir Gerard.

Some weeks ago, I was visited by the Greek Minister, Kallerges, who proceeded to tell me that he had just been

informed by Wangenheim of a plot against the King with the connivance of Austria. I at once doubted this as I

could see no reason — other than feelings of personal friendship towards Kallerges — as to why the German

Ambassador should implicate his Austrian ally. Yet Kallerges laid such great emphasis on the probity of the

Ambassador that I began to suspect that a plot had been hatched, but which ran counter to German ambitions for

the region. From other information I have been able to gather, I now believe that Vienna hoped to take advantage

of the confusion to make a grab for territory, particularly at the expense of Serbia. If the crime could be laid at the

door of the Serbs or Bulgarians, Vienna hoped by such means to set one Balkan ally against the other. To restore

order, the Austrians planned to march into Salonica.

Such a scheme would have been, as you are doubtless aware, fraught with danger. And the greatest danger for

Germany would have been to have been dragged into such an imbroglio by the rashness of her ally. A war now

would come too early for Wilhelm — better to give diplomacy a chance. The Turks and Bulgarians are almost won

over to the German cause; Greece will be next. By informing the Greeks therefore, through Wangenheim, that an

assassination is planned, Wilhelm accomplishes two things — first, the Austrian scheme, with all its attendant

dangers, is nullified; second, he portrays himself as the champion of the Greeks (even if this does prevent his

brother-in-law from gaining the throne!). For these reasons, I believe that Wangenheim was not dissembling and

that the warning was accurate. Kallerges certainly was of opinion that the attempt would be made, and has duly

warned Athens.”

Crowe folded the letter, tapped it on the desk a few times, and then slowly pushed back his chair. He made to

stand, then resumed his position, pulled the chair to the desk and reached for pen and paper. The Assistant

Under-Secretary quickly made a copy of the letter.

As another shower scudded in from the east, in the warmth of the Admiralty building Prince Louis of Battenberg,

the First Sea Lord, burst in on his chief, Winston Churchill. It seemed difficult to appreciate that the pink cherubic

figure seated behind the enormous desk could arouse such divided feelings. He could be infuriating; he could be

brilliant; he could be petulant and childish. Prince Louis was prepared to forgive him his faults however, as

Winston clearly had the best interests of the Navy at heart. If only he would refrain from needlessly upsetting the

older Admirals on the list. Beresford, for example, was an opinionated, crushing bore; but he still had powerful

allies and needed to be cultivated, not alienated. However, so long as Winston maintained his supposedly discreet

association with Fisher (while Winston took great pains to keep all their meetings secret, Fisher delighted in

telling all and sundry that he had the private ear of the First Lord of the Admiralty), he would never get anywhere

with Beresford.

‘First Lord, this F.O. wire has just come through. King George has just been mortally wounded in Salonica.’

The news did not seem to take Churchill by surprise; but this was simply his method of appearing at all times to be

in control. ‘Do we have a motive?’

‘None has yet surfaced. It seems odd that, by all accounts, a Greek has pulled the trigger.’

‘The King was our man, wasn’t he?’ Churchill then casually inquired.

‘Yes. The Balkan position was as secure in our favour as ever it could be while George remained on the throne. Of

his heir, I am not so sure. By all accounts Constantine is his own man but he is also, as you know, the Kaiser’s

brother-in-law. I believe it to be inconceivable that he will not come under intense pressure from that quarter.’

While Prince Louis talked, Churchill tried to recall the myriad strands of European royalty. Why was there so

much intermingling? It did not, he silently assured himself, contribute to keeping the peace; in fact, almost the

reverse. Who doubted that the German Kaiser’s almost pathological envy of Britain did not stem from having

Queen Victoria as his grandmother? And the Glücksburgs, the Danish royal family imported into Greece in 1863,

had been as calculating as any in their choice of partners: George’s sister was Queen Alexandra of Britain;

George’s son Constantine had married Sophie, the Kaiser’s sister. However, there was one liaison which might

now work in their favour: Constantine’s younger brother Andrew had married Battenberg’s own daughter, Alice.

Churchill looked up at the dignified, erect, blue-bearded figure before him, the very model of an admiral (for he

could have been nothing else), and, as insouciantly as possible, as he perhaps knew what the answer would be,

inquired: ‘Have we any method of countering such pressure? Your daughter, perhaps?’

Although he had been expecting the question to be put, Battenberg still frowned at the proposition: ‘No, First

Lord, I would prefer to leave her out of this. If Constantine is to be influenced it will have to be by some other

means.’

‘Do you have any suggestions?’ At that, the flicker of a smile flashed across the face of Prince Louis. A less

observant onlooker might have mistaken it for a twitch, but such things did not escape the attention of the First

Lord. ‘You clearly have some devious plan hatching,’ Churchill continued. ‘Should I know about it?’

‘Not a plan, First Lord, and hardly devious. Call it, instead, an “opportunity”. The Greeks, as you know, employ a

British Naval Mission for training and other purposes. Although the current Balkan War will soon end, at some

future time the Greeks will again fight the Turks, of that I am sure. We also have a Naval Mission in place in

Constantinople … ’

‘Yes,’ interrupted Churchill. ‘A curious state of affairs when we are training both sides to slaughter each other.’ He

recalled the feeling of revulsion he had experienced when news had first come through of the massacres

perpetrated upon the indigenous population of Libya by the so-called civilized Italians, whom he, initially, fully

supported. He was as upset as anyone — it was simply not true that he was a war monger.

Ignoring the First Lord’s momentary fit of scruples, Prince Louis continued: ‘The Greeks are a jealous peoples.

They feel, rightly or wrongly, that, as the maintenance of the Ottoman Empire is of more importance to us than a

strong, independent Greece, we have placed officers of a better calibre in Constantinople. I understand that they

refer to our men in Athens as “Naval Pensioners” and have refused to renew the contract of Admiral Tufnell,

which has just expired. Personally, I believe there is some substance in this allegation. I would not be unhappy to

secure for them an officer who viewed his tenure there as an opportunity to be seized, rather than as a comfortable

sinecure in preparation for retirement. Now … ’ And here there was a very deliberate, measured pause, ‘ … if we

could also ensure that that officer followed our instructions to the letter and was known personally to Constantine

there might be some chance that the new King could be steered towards at least tacitly supporting our Balkan

policy.’

Churchill leaned back: ‘Do we have a Balkan policy? If so, I would be grateful if you could explain it to me.’ Prince

Louis did not rise to the bait, leaving Churchill petulantly to inquire: ‘Do we possess such an officer?’

‘Yes, First Lord, we do. Mark Kerr. He is known to me personally. Not only is he an able officer but more

important he has known the Greek Royal family for twenty-five years. As a matter of fact he was with me in

Athens in ’89 for the wedding of Constantine and, I believe, he has kept in touch with the Prince ever since.’

‘Kerr?’, mused Churchill carefully as he obviously tried to recall something. ‘Kerr? I know the name. A member of

your own secret coterie, isn’t he? Did not Jacky Fisher try to foist him on me when I first came to the Admiralty?’

For all his childlike enthusiasm upon entering the Admiralty, Churchill had been careful not to be overly swayed

by Fisher’s relentless “suggestions”. Indeed, he had taken great delight in rejecting all the names Fisher had put

forward; he was to be his own man.

If Battenberg was affronted by this reference to his close friend he did not show it: ‘ “Foist” is hardly the right

word, First Lord. But you are correct: Kerr has been, in addition to his usual duties, operating in a secret capacity

for some years.’

Though he would not admit it, this aspect of Admiralty work fascinated Churchill, a fact on which Battenberg was

counting. The First Lord sat upright, his eyes fixed firmly on Prince Louis: ‘Pray, enlighten me.’

‘In the course of his duties, Kerr has, at various times, come into close contact with our friend in Berlin. The

Kaiser is, in fact, godfather to Kerr’s daughter. It seemed a pity to waste such an opportunity, so we decided to use

Kerr as a conduit through which we could channel information that we knew Wilhelm wished to hear, but which,

at the same time, was somewhat less than accurate.’

‘We?’ growled Churchill. ‘So Fisher was involved?’

‘Sir John never set great store in an organized and politically controlled Secret Service. He much prefers, as you

know, to be in complete command himself. He liked to boast when here that, when necessary, he could have

information, as he put it, ‘whispered in the German Emperor’s ear’. When I was D.N.I.* during Sir John’s tenure

he soon decided that, Tirpitz apart, the German navy owed its being to the Kaiser. He was confident upon

assuming office that with our preponderance in older vessels and our ability to outbuild Germany on a ship for

ship basis our supremacy would remain unchallenged. Until, that is, the advent of Dreadnought and Invincible.

Such vessels, naturally, rendering all other line of battle ships obsolete at a stroke, meant that we would both be

starting from the same line whereas Sir John always favoured the handicap system.’ Battenberg broke off

momentarily and fixed his gaze on the painting of Dreadnought which graced the far wall of the First Lord’s room.

‘He determined to do something, but soon came to realize that there was little opportunity to disguise our

intentions with Dreadnought; Invincible, however, was another matter. The battle cruiser class always was closer

to Sir John’s heart. He told me privately at the time that he only agreed to the laying down of Dreadnought on the

condition that he could have his three Invincibles. Yet, as far as the Germans were aware, Invincible was simply

another large cruiser, a natural progression from the previous class; they had, we were convinced, no idea as to

her true firepower and speed. We therefore determined to confirm their belief.’

The First Lord shifted in his seat and began to fidget with a pen. ‘I am not sure I want to hear this.’

Battenberg ignored this plaintive request: ‘It was quite simple really. We had two sets of plans made; one for us

and one for them. Ours were, of course, accurate in every detail. Theirs rather underestimated the calibre of the

main weapons and the speed.’

‘And where did Kerr fit in all this? Why was this not brought before the Defence Committee?’

Battenberg ignored the latter question. ‘Kerr, at the time Captain of a small cruiser, struck up an acquaintance

with a person we knew to be one of their agents. It had to be done carefully. At first Kerr was of little interest to

the agent. Then, as part of the plot, he was assigned to the Admiralty in an unofficial capacity to acquaint himself

with the details of the new ship, as it was proposed to name him as the first captain of Invincible. This meant he

was allowed legitimate access to the plans. As time was pressing, he was even encouraged to study them at home,

though only one section at a time. We anticipated that, if the agent, who was in receipt of invitations to Kerr’s

home, chanced upon a complete set of plans, even he might wonder at his good fortune and wonderment would

turn to suspicion. But if he could view the faked plans, piecemeal, all the while thinking himself clever to have

infiltrated the Admiralty, then, we reasoned, there was all the more chance that the ruse would work and they

would be accepted as genuine.’

‘And the result was Blücher.’

‘Precisely, First Lord. Inferior in every way to Invincible.’

Churchill pounced at once upon the obvious objection: ‘Surely, however, upon discovering the ruse, Kerr’s value

for such future escapades would be instantly compromised.’

‘We also thought of that. Kerr, with his connections in Berlin, was too valuable to waste. We …’ Battenberg

paused, as the memory of the episode returned and, with it, his delight at the outcome of the operation. ‘We let it

be known in the right circles, through our own agent in the German Admiralty, that their man had double-crossed

them. He had, so our agent maintained, stolen the real plans and sold them to the Russians, but not before

making a fake set, which he then sold to the Germans.’

‘That is despicable,’ Churchill declared not very convincingly, while sharing in Battenberg’s delight. ‘I assume the

German agent found his working days at an end?’

‘He disappeared while travelling on the steamer from Ostend to Harwich. His body never was found.’

‘So Kerr remains untainted?’

‘Yes; if anything, his value to us has increased. The Germans, who never suspected his involvement, recognized

that, having been supposedly duped once, the same operation might be undertaken once more, using a more

reliable agent. And, since the Invincible episode, Kerr has taken pains to cultivate the Kaiser. We made sure he

was in Corfu in ’08 for Willy’s visit and, at our prompting, he suggested to the Emperor that it would be a useful

exercise if they corresponded. You know how fascinated Willy is by all things nautical. This gave Kerr the excuse

to write a series of, how shall I put it, rather indiscreet letters reporting on so-called advances in the engineering

field and mentioning, I am afraid, the opinions of certain Cabinet Ministers with whom he had spoken.’

‘Precisely what sentiments have you been putting into my colleagues’ mouths?’

‘Oh, dropping the “Two Power Standard”; that sort of thing.’

The First Lord spluttered involuntarily. ‘I trust, Louis, that you have this firmly under control?’ Battenberg shifted

uneasily, clearly intent on framing his answer. ‘First Sea Lord?’ Churchill demanded in a menacing tone.

The First Sea Lord looked Churchill directly in the eye: ‘Kerr has, at times, been a little inclined to take his duties

too seriously.’

‘How inclined?’

‘He has, for example, on occasion reported your own opinions to the Kaiser. Or what, I should say, he believes the

Kaiser wishes to think is your opinion.’

Churchill leaned back. His restless eyes wandered along the walls of the First Lord’s office. There, set out before

him, was a painted history of British naval mastery. Once more, the navy, his navy, was engaged in a life or death

struggle with an adversary who, on current estimates, would match the Royal Navy ship-for-ship in a matter of

years. The situation was too serious to accommodate such amateur fumblings. He must put a stop to this. ‘If —

and it remains for the time being, an ‘if’ — Kerr does go to Athens, to head your Naval Mission, what guarantee is

there that he will not, similarly, become carried away? His allegiance must be to us and to us alone; is there not a

danger that he might become too closely associated with the Greeks in such a post?’

Battenberg breathed more easily; he had known all along that Churchill could not resist such a scheme. ‘I think I

can give that assurance, First Lord. I myself will tutor Kerr on his responsibilities. Nothing will go wrong. If it

works, we can, at best, count on Greece siding with us in any future Balkan difficulty. At worst, their neutrality is

assured.’

‘And if it doesn’t work, you, Louis, will pay the penalty.’ Battenberg started; he had not counted on this; he knew,

better than anyone, Kerr’s overabundant romantic streak. If they fell, they would fall together. ‘Returning to the

issue at hand,’ Churchill continued, ‘how do you propose that we elicit from the Greeks an offer to renew the Naval

Mission?’

‘I have made some preliminary inquiries, and I am convinced that Stratos, their Minister of Marine, is sound. He

is on our side. I believe a personal approach from you, First Lord, would have the best chance of succeeding.’

‘And when do you suggest would be the proper moment at which to make this personal approach?’

‘When are we scheduled to embark on Enchantress, First Lord?’

Churchill grinned: ‘I suspected as much.’