The Traitor

A novel of Betrayal

As the range of our activities is so diverse, we have a number of different websites. The main Flamborough Manor

site, which is where you are now, focuses primarily on accommodation (bed & breakfast) but has brief details of all

our other activities. To allow for more information to be presented on these other activities, we have other self-

contained web-sites and some of the links you will encounter while browsing these pages will take you to these

separate sites. To return to this site, simply go to the LINKS page, which is common to all our sites.

Views of Flamborough Head

The Manor House, Flamborough, Bridlington, East Riding of Yorkshire. YO15 1PD

Telephone: 01262 850943 [International: +44 1262 850943]

E-mail: gm@flamboroughmanor.co.uk

Web-site design & content Copyright © 2024 Geoffrey Miller

Based on "Superior Force" the acclaimed

study of the escape of Goeben and Breslau :

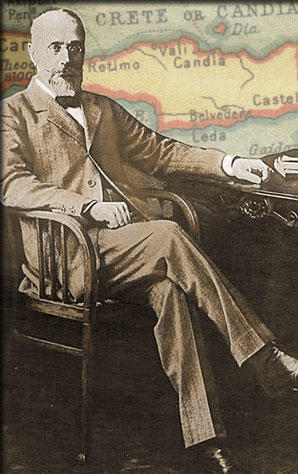

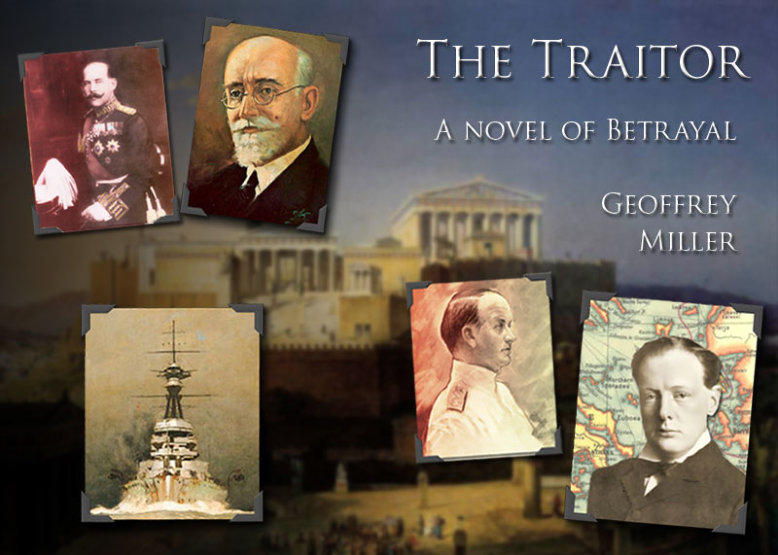

"The Traitor" is firmly grounded in fact. The majority of the people referred to in the novel took part in the actions described. Many of the conversations are based on diary entries, memoranda and letters subsequently published by the main protagonists. The principal exception to this is the character of Major Lionel Samson. When he first appears, Samson is, as he was in fact at the time, the British Military Consul at the siege of Adrianople in 1913. By 1915 he was, in real life, in charge of the allied espionage network based in Athens. However, between these two dates, all actions ascribed to him in The Traitor are fictional. On the other hand, the other main character, Admiral Mark Kerr is portrayed throughout as he was during the period. His actions, however implausible, are firmly based on the research gathered for my non- fiction studies of the events of this period, Superior Force, Straits and The Millstone. During the first week of August, 1914, Admiral Mark Kerr faced a desperate choice: betray his conscience or his country. It was a choice he faced in real life, where his attempt to reconcile the competing demands of his service to Britain and Greece failed. Major Lionel Samson’s principal experience of betrayal stemmed from a more personal encounter: an affair which ends when fate (according to Edith Roberts) intervenes. The sense of loss — and betrayal — Samson feels is heightened as, at that time, he does not believe in fate, or the pre-ordained workings of some exterior force, either for good or evil. Forced to reconsider his own deeply held beliefs, Samson is also disillusioned when everyone he encounters in Athens appears to operate on two different levels, and betrayal, at both personal and official levels, is rampant. Professor Geroulanos, for example, while certainly calling himself a Greek patriot, belongs to an organization whose only aim is the furtherance of German influence in his country (another example of the activities of a real-life character being mirrored in The Traitor). Even within the confines of the British Legation Samson comes to suspect that senior officials are hiding something. And, finally, the agent he employs is also working for someone else. Samson is forced to consider the prospect that the ability to betray, to lie at will, is part of man’s nature. Then, however, his life is saved by the same Professor Geroulanos he suspects of treason; his closest ally within the Legation is converted to share his suspicion regarding the Greek Premier; and his own agent, the Greek porter, posthumously provides the evidence to help resolve the final part of the puzzle — the identity of the traitor. Samson is almost re-converted into disbelieving the workings of a malign fate until a moment’s cowardice, which he later excuses by reasoning it was pre-ordained, results in his final test.

The Manor House

Accommodation, Books, Traditional Knitwear & Hand-Knitted Ganseys, Breton shirts

Lesley Berry and Geoffrey Miller

The Manor House

Flamborough

Bridlington

East Riding of Yorkshire YO15 1PD

United Kingdom

Telephone: 01262 850943 (Mobile 07718 415234)

International: +44 1262 850943

E-mail: gm@flamboroughmanor.co.uk

Chapter 1 The Disappearance

Chapter 2 Rusa Bay

Chapter 3 Salonica

Chapter 4 Whitehall

Chapter 5 The Enchantress

Chapter 6 Avret Hissar

Chapter 7 Scutari

Chapter 8 The Secret Meeting

Chapter 9 The Offer

Chapter 10 The Pension Merlin

Chapter 11 The Stooped Man

Chapter 12 Professor Geroulanos

Chapter 13 The Missing Report

Chapter 14 The Greek Colonel

Chapter 15 Visarionos Street

Chapter 16 A Death

Chapter 17 The Asylum

Chapter 18 Motives

Chapter 19 An Intruder

Chapter 20 The Piraeus

Chapter 21 The Fatal Meeting

Chapter 22 Allegiances

Chapter 23 The Journey

Chapter 24 Naval Matters

Chapter 25 A New Beginning

Chapter 26 The Notebook

Chapter 27 Departure

Chapter 28 Constantinople

Chapter 29 The Banquet

Chapter 30 Return to Athens

Chapter 31 The Adramyti Plan

Chapter 32 War

Chapter 33 Bogados

Chapter 34 Messina

Chapter 35 The Traitor

Chapter 36 The Last Letter

SYNOPSIS

The opening two chapters of The Traitor are set in August 1914 when Major Lionel Samson, a British Military Consul, is forced to observe impotently as the German battle cruiser Goeben is able to coal in a secluded location in the Aegean and so complete her fateful journey to the Dardanelles. As he watches, Samson goes back over the events of the previous seventeen months, commencing with the disappearance of his lover Edith Roberts in Smyrna in October 1912, through to the assassination of the Greek King George in Salonica in March 1913. This act brings to the Greek throne his son, Constantine, who was both educated in Germany and is married to Kaiser Wilhelm’s sister. As such, the obvious belief in London is that Athens, thenceforward, will follow a policy aligned to the ‘Triple Alliance’ of Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy, notwithstanding the presence of the pro-Entente Premier, Eleutherios Venizelos. The Admiralty reaction to this is to send Admiral Mark Kerr, who is known personally to the Kaiser, to Athens as head of the British Naval Mission assisting the Greeks in the creation and training of their new fleet. The hope is that Kerr, by his influence at Court, will help to counter the pressure it is assumed will be applied to Constantine from Berlin. Simultaneously but independently, the Foreign Office in London is apprised of a rumour from Constantinople that the assassination was not the irrational act it first seemed, and that leading circles in Athens were forewarned. Realizing that, if this is the case, Venizelos must be implicated, and it is upon his trust in Venizelos that the Foreign Secretary bases his Balkan diplomacy, Sir Edward Grey determines that he must have a secret source in Athens reporting on events. This is the task given to Major Samson. Samson sets off from Adrianople with the intention of travelling first to Salonica and then by steamer to Athens. While crossing Macedonia, however, he comes across a German archaeological dig at Avret Hissar, a site of little apparent interest. His suspicions are immediately aroused. Once in Athens Samson begins his investigations. These quickly lead to the German Archaeological School and the School of Surgery at the University of Athens, where the assassin once taught. It appears initially that a rumour of Austrian involvement in the assassination is correct: hoping, thereby, to be able to further their own territorial ambitions, a scheme had been hatched in Vienna to assassinate the Greek King in the knowledge that he would be succeeded by his Germanophile son. Although planning commenced, it was supposedly called off as a result of pressure from Berlin. Samson, unsure whether this is a cover story, seeks permission to interview the assassin in the insane asylum to which he has been confined. At this interview the facts behind the assassination are revealed, but not the rationale. As he begins to unravel the various strands of the mystery, Samson learns that the Greek Government’s investigator, Triantafyllakos, has written a report detailing the full extent of the conspiracy. However, before the Greek can pass this information on to Samson, he is murdered. As his own investigation progresses, Samson becomes increasingly disillusioned, haunted by a past love affair. In this frame of mind, when he learns that a large cache of Turkish arms, known to have been delivered to Salonica, has since disappeared, he is certain that the key to the mystery is at Avret Hissar. By enlisting as his agent the Greek porter at the German Legation, Samson is able to provide both London and his own Legation in Athens with information on German intentions. It is through the agency of the Greek porter that Samson learns that his opposite number, the German agent Hoffman is active, and also that there is a Greek traitor, supplying information to the Germans. Acting without official help, Samson is unable to uncover the identity of the Greek traitor, although he does learn that a surprise Bulgarian attack upon Greece will soon be launched, but will be countered by the Greeks, with the use of the missing Turkish weaponry. The Greeks hope to ambush the Bulgarians at Avret Hissar. Samson travels to Avret Hissar where, as the battle opens, there is a confrontation between Samson and Hoffmann at which Samson is dangerously wounded. His life is saved by the Greek surgeon Geroulanos, whom Samson suspects of involvement in the murder of Triantafyllakos and the Major returns to Athens to recuperate. During this time he falls in love with Rachel Summers, married to one of the officers of the British Naval Mission; however, realizing the hopelessness of the situation, and still haunted by the disappearance the previous year of his great love, Edith Roberts, Samson longs to leave Greece. With the arrival of Admiral Kerr at this time, the balance of power within the British Legation alters. In his first meetings with the Prime Minister, Kerr develops an instant dislike of Venizelos. In part this is due to a different perception of the course that Greek naval expansion should follow; it is also a result of Kerr’s infatuation with the very idea of kingship. Kerr soon joins the court faction, along with the Military Attaché, while the majority of the British diplomats still back Venizelos. As tension begins to increase with Turkey, following the end of the Balkan Wars, Kerr goes about his job, developing the Greek Navy while Samson, ill physically and mentally, returns to Constantinople to regain his strength. This is the situation in June 1914 following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. As the crisis develops in July, King Constantine comes under intense pressure to join Germany and Austria in declaring war. The King is adamant however that neutrality is the only sensible option for Greece. He successfully convinces Kerr who agrees to support him. Ordinarily this would mean no more than sending slanted reports to London. This position changes radically on 4 August 1914 when Constantine is informed by the Kaiser that the two German warships in the Mediterranean (including the powerful battle cruiser Goeben) have been directed to Constantinople to join the Turkish fleet. Kerr now faces an agonizing choice: he has, in the period of his tenure in Athens, become wholly devoted to the Greek cause. He is convinced that Constantine is right and that neutrality is the only course for Greece to follow. However, if he divulges the information which he is now also privy to, and the German ships are intercepted and destroyed by the more powerful British Mediterranean Fleet, a declaration of war by Germany against Greece is certain to follow. Kerr’s choice (a choice he had to make in real life) highlights the central moral issue of the book: the theme of betrayal. Eventually, after waiting three days, he formulates a scheme by which he hopes to circumvent the Kaiser’s threat. He informs the Russian Minister in Athens of the ships’ destination, so that when the intelligence is routed via St Petersburg and Paris (as he knows it will be) the source will be sufficiently disguised. What he does not count on is that the message, which he has left deliberately vague, is not deemed urgent and is delayed in getting through. A second scheme, in which the German ships are apparently located innocently by direction finding equipment also fails. Meanwhile, Samson, against his better judgment, had been ordered to return to Athens, as there are fears that the Greeks will launch a pre-emptive strike against the Turkish Navy. While Kerr’s mental torment continues, Samson has discovered that a consignment of German coal is being loaded aboard a collier at Piraeus on the instruction of Venizelos. In an attempt to discover its destination, he slips aboard looking for any paperwork which might provide a hint. However he is trapped aboard by Hoffmann as the ship sails and remains in hiding. The collier is in fact carrying coal for the German ships, which, although being pursued by the British fleet, have a day’s start. Not having enough coal to reach the Dardanelles the German admiral decides to use one of the many Greek islands as cover, while he coals. It is to this rendezvous that the collier proceeds. As the coaling takes place Samson is a mute witness. He has discovered the destination of the German squadron but cannot relay the information to Athens. Rather than risk capture, he swims to shore and has to await rescue, by which time Goeben has reached the Dardanelles. While casually reassessing the evidence awaiting rescue Samson believes, at last, that he knows the true identity of the traitor. Once back in Athens he confronts his suspect, a confrontation which forms the climax of the novel.THE BALKANS

MARCH 1913

At the turn of the century the moribund Ottoman Empire still exercised a tenuous sovereignty over much of south-eastern Europe. Greeks and Serbs, Bosnians and Albanians co-existed in an uneasy mix, their mutual contempt for each other only held in check by their greater loathing for their Ottoman overseers. All this was to change in 1908. The long and oppressive reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid — Abdul the Damned of popular legend — was to end, against expectations, in a bloodless revolution (or as bloodless as these things ever are). Seizing their chance, following the upheaval caused by the Young Turk revolution, in October 1908 the Austrians (after the Italians, and due to their lack of confidence in their Great Power status, the most cynical players in the game of diplomacy) formally annexed the provinces of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which were still nominally Turkish. Simultaneously, Bulgaria, whose undisputed status as a very minor power excused such opportunism), declared her independence. These actions provided the signal for the rise of Albanian and Serb nationalism and made the collapse of Turkey-in-Europe ever more likely. Envious and covetous in equal measure, the Greeks longed for their chance. Too weak militarily to force the issue at the time the Greeks sought strength on land through a system of loose alliances with neighbouring states and strength at sea through a revivified navy. Adding a sense of urgency to the plans for Greek re-armament was the increasingly parlous state of the Ottoman Empire, which, by 1911 was beginning to crumble — a lumbering wounded animal surrounded by snapping dogs. Ironically, the certainty of the Empire soon becoming involved in a war was only partly offset by the surprise felt that it should be the Italians who began the process of dismantling the Empire. Using the excuse of long standing ambitions on the African littoral Rome declared war on Turkey on 29 September 1911. The first hole had been gouged out of the ramshackle edifice of the Ottoman Empire. It should come as no surprise, however, that Italian military ambitions did not live up to Italian diplomatic ambitions; the fighting was anything but one-sided. Eventually, after protracted negotiations a treaty of peace, recognizing Italian sovereignty over Libya, was signed on 18 October 1912. But Turkey had finished with one war only to be embroiled, before the ink was dry on the peace treaty, in a far more dangerous conflict against that unholy alliance, the Balkan League. What one alone could not accomplish, together the uneasy allies hoped to achieve. The attempt to reconcile the competing aims of the restless states was only partially successful: the Serbs, above all, desired an outlet to the sea; the Bulgarians and Greeks looked to carve up Macedonia between them; and King Nicholas of Montenegro? Well, Nikita wanted whatever he could lay his hands on. Tension mounted throughout the summer of 1912, fanned by further Albanian unrest, until, finally, the Balkan League mobilized on 30 September. By arrangement (or so it was thought at the time), Montenegro made the first move, declaring war on Turkey on 8 October; Serbia, Bulgaria and Greece followed suit on 17 October. From the start the war went disastrously for the Turks as three of the four members of the League quickly marched to their respective primary objectives: before the end of the month, the Montenegrins had invested Scutari and the Serbs had besieged Uskub, while Salonica surrendered to the Greeks on 8 November, just hours before a flying column of the Bulgarian army arrived. In the interim the two sets of troops of the erstwhile allies warily occupied the city. Meanwhile, the bulk of the Bulgarian army, involved in the heaviest fighting and directed against the main Turkish army rather than towards easy territorial conquest, had invested the strategic city of Adrianople (modern Edirne) by 23 October, when it appeared that the fall of the Turkish capital could not be long delayed. Finally, the last bastion of defence for Constantinople – the Tchatalja lines – is assaulted by a massive Bulgarian attack in mid-November, despite an earlier request by the Turks for an armistice. To general surprise, the Turkish lines held. Following this unexpected check and a perhaps more predictable outbreak of cholera amongst their troops, the Bulgarians were forced to adopt a more conciliatory tone and (in conjunction with the Serbs) an armistice was arranged on 3 December; the Greeks, however, refused to sign as they wished to continue their naval blockade. Despite this cynical Greek opportunism, all the warring states sent representatives to the St James’s Conference which convened in London on 16 December. Taking advantage of the armistice, the Turks regrouped and gathered strength behind the Tchatalja lines while remaining in possession of Adrianople, Scutari and Janina. Past military disasters were soon forgotten, to be replaced by a new-found belligerency, as the Turks refused to lie down and submit following the coup d’etat in Constantinople which brought Enver Pasha and his cohorts to power. However, with the expiration of the armistice on 3 February 1913, the bombardment of Adrianople recommenced and, one by one, the Turkish garrisons began to capitulate.

This is the mobile variant of our web-site, specially designed for

viewing on smartphones, but lacking some of the more detailed

information available on our full-size site..

Views of Flamborough Head

Web-site design & content Copyright © 2019 Geoffrey Miller

The Manor House

Accommodation, Books, Traditional Knitwear &

Hand-Knitted Ganseys, Breton shirts

Lesley Berry and Geoffrey Miller

The Manor House

Flamborough

Bridlington

East Riding of Yorkshire YO15 1PD

United Kingdom

Telephone: 01262 850943 (Mobile 07718 415234)

International: +44 1262 850943

E-mail: gm@flamboroughmanor.co.uk

The Manor House

Flamborough

Bridlington

East Riding of Yorkshire

Telephone

01262 850943

The Manor House, Flamborough, Bridlington, East Riding of Yorkshire. YO15 1PD

Telephone: 01262 850943 [International: +44 1262 850943]

E-mail: gm@flamboroughmanor.co.uk

Web-site design & content Copyright © 2024 Geoffrey Miller